Software Development Best Practices

What are software best practices, really?

Unit tests. Integration tests. Smoke tests.

Code reviews. Continuous deployment. Corrective actions. Change management templates.

Agile. DevOps. Infrastructure as code. Observability, monitoring, and logging.

Containerization. Serverless. Reproducible environments. Development environments.

Test-driven development. Hammock-driven development.1

Object-oriented design. Domain-driven design.

Pair programming. Site reliability engineering. Two-pizza teams.

Microservices. Monoliths. Modularity.

Design documents. Domain-specific languages. One language to rule them all.

Speed matters. Slow and steady wins the race.

Engineers as leaders. Managers as engineers.

People over process.

Are we done?

The Problem with Nouns

We are not done. Besides the self-contradictions, there is obviously something hollow in the nouns (and slogans) above.

When should we write integration tests? When should we go slow and steady, and when should we sprint? How do we do code reviews and design documents? What should we monitor and log? When is a monolith the right answer, and when is a microservice better? How should an engineer be expected to lead, and a manager expected to operate as an engineer?

Any best practice worth its bits should help us wrangle the nouns into complete ideas.

The hard part is generality.

Teams commonly assemble specific answers to these questions, based on very specific people and contexts and requirements: “Our team’s standard is 80% unit test coverage,” “We use microservices on this team,” “We don’t typically write integration tests due to the instability of the staging environment.” But this practice fails catastrophically to incorporate the collective experience outside of the team and outside the company from other people who have faced variants of the same questions and problems.

With that in mind, the rest of this essay is an attempt to chart a Middle Way between empty nouns and specific team conventions.

Back to Basics

Computer programming ultimately comes down to translation of human work that could be done on pencil and paper (any Turing-complete notation system will do2) into repeatable, faster processes that can be done partially or entirely by a computer.

Therefore, the fundamental question in software engineering is one of ordering: which parts of the human work to automate first.

And to answer that question, there is one obvious general rule:

Rule 1: Prioritize automating the repeated work that would take the most human time to complete.

How do we know what is repeated the most and what would take the most time?

Approach 1 (The “Outside View”): Measure how our time is spent, look for patterns, and generalize.

Approach 2 (The “Inside View”) : Develop models on which types of work tends to be repeated and what types of repetition tends to take the most time; use those models as heuristics.

Approach 1 is a standard focus of software product management; the designers of software systems look for existing human workflows and seek to automate the most laborious parts. The more work saved, the better the justification for writing software to automate it.

But it also has fundamental shortcomings. First, it is backwards-looking; it doesn’t account for the dynamic nature of work or look ahead to future sources of repetition. Second, it becomes decreasingly tractable at higher levels of abstraction. To take an example, it may be possible to measure how much time an engineer spends configuring her software development environment, but harder to reliably measure how much time is spent repeatedly onboarding engineers to a new team, or repeatedly transferring team domain knowledge from one engineer to the next. One could go to an even higher level of abstraction: how much time is spent rebuilding systems that were previously built with incorrect requirements, repeating the same categories of mistakes, or repeatedly re-discovering the same software engineering principles by trial and error? These are intuitively the costliest forms of repetition, but there is no way to expect a purely empirical answer to them.

This is where Approach 2 comes in.

Compounding

“Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world.”

- Albert Einstein

Why do so many fundamental trends of the economy – world GDP growth, Moore’s Law, solar power price-performance, storage costs, AI price-performance, etc. – take on exponential curves?

At the core of these trends is the concept of compounding, also described as the “flywheel effect”3 or the “Law of Accelerating Returns”4:

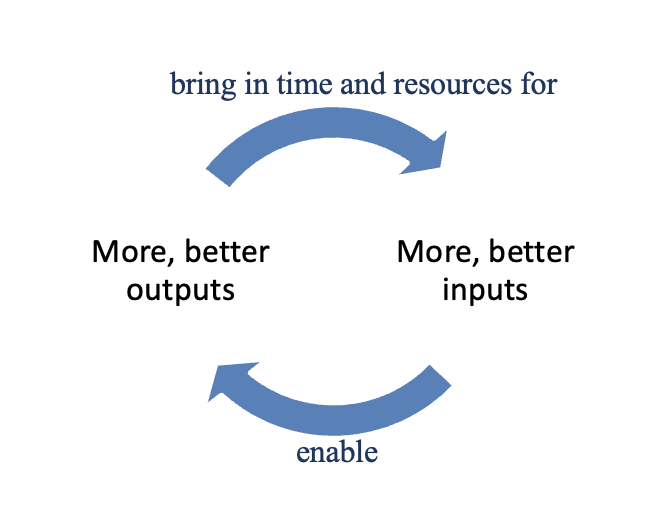

**Figure 1: Compounding**

Each time the cycle completes, it becomes faster and/or more powerful, leading to the exponential effect. (In Einstein’s case of compound interest, principal is the “input” and interest is the “output.”)

What does this have to do with software engineering best practices? It provides an elegant and powerful starting point for Approach 2. I’ll simply make the claim here: compounding is the single most important conceptual model for understanding progress in technology. Therefore, it should be the starting point for any model on how to sequence automation in the context of software engineering.

From this, a first principle:

Principle 1: The central principle of software engineering is to sequence work in a way that creates cycles of compounding, such that prior automation accelerates future automation.

(This is very closely related to commonplace “don’t repeat yourself” (DRY) rule of software engineering.)

Unlike Approach 1, it’s not empirical, because it requires making forecasts about future work. But it satisfies Rule 1: when the “object” of engineering is a cycle of compounding, applying the principle requires (by definition) that more time is saved with each revolution of the cycle.

A canonical example in software engineering goes as follows: a high-quality automated integration testing framework (input), allows engineers to test and deploy software more rapidly (output), giving the engineers more time to make further improvements to the testing framework, allowing the next deployment to go out even more rapidly, ad nauseum, in a beautiful, virtuous cycle of compound acceleration.

(It’s worth mentioning that the end-product in question (say, a web service with REST APIs) may itself be an input or a tool for other processes (say, an inventory management system) – and so in practice, cycles of compounding are naturally multi-layered, interconnected, and recursive.)

Decomposing the Inputs

With Principle 1 in hand, it’s now possible move down into a more practical adaptation. To do this, we break down the general category of “inputs” to the compounding cycle into more specific sub-groups: technical tools (for producing software systems), plans (for producing end-products), technical knowledge (for producing plans and for execution), and principles and tenets (for producing plans).

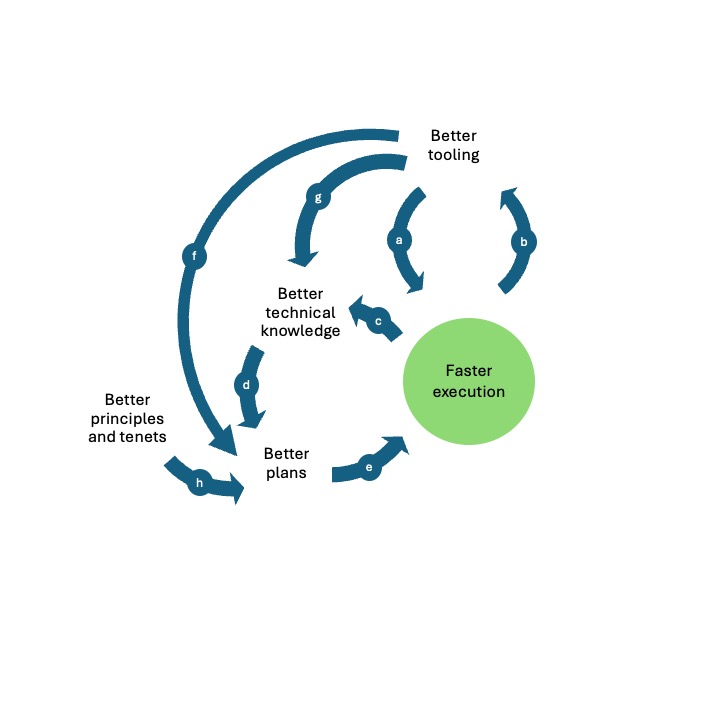

This can be represented by interconnected compounding cycles:

**Figure 2: Compounding in the context of software systems**

Each labeled arrow represents a pathway where there are concrete, knowable, documentable feed-forward mechanisms. Some more elaboration on each arrow:

a. More powerful software tooling eliminates repetitive manual labor, leading to faster execution.

b. Faster execution frees up engineering time to build better tooling.

c. Faster execution frees up engineering time to learn more deeply and widely.

d. Better technical knowledge leads to better technical designs and plans.

e. Better technical plans lead to less wasted rework and therefore faster execution.

f. Better tooling in the form of documented design processes, standards, guidelines, and templates lead to better designs.

g. Better learning management systems improve individual technical knowledge.

h. Better principles and tenets improve planning by means of applying distilled, collective knowledge.

It’s worth mentioning that “tooling” is doing a lot of work in this system – in the form of not just standard software “build” tools, but also in the form of templates, learning software, and design templates and conventions. “Tooling” is ultimately a broad and essential category, as any software engineer will appreciate.

Of course, this is not science. These circles and arrows do not somehow emerge from the laws of physics, and they are not the only forces as work. But just like the famous Amazon flywheel, this essay argues that such a model can help orient work towards closing loops and understanding work not just as a sequence of steps but as the engineering of a self-sustaining system.

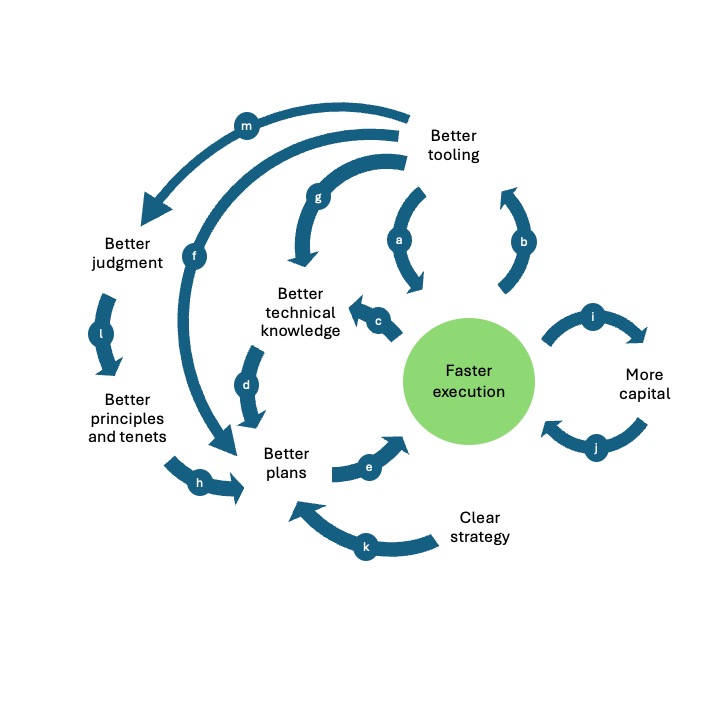

Putting the Flywheel in Context

As much as we may wish otherwise, software systems do not exist in the Platonic space of pure ideas. There also happen to be people, and capital, and business objectives and strategies. With just a little extra work, we can add this “context” to complete the flywheel (Figure 3). There are now a few more arrows to describe:

i. Faster execution generates more capital.

j. More capital speeds up the flywheel generally by fueling the whole system with resources.

k. A clear business strategy makes it easier to form effective plans.

l. Principles are cheap. People and teams with collectively good judgment know how to cultivate, improve and apply them effectively.

m. Good tooling can help track the quality of judgment and elevate people and teams who exercise good judgment.

**Figure 3: Compounding in the context of a software engineering organization**

One point: Figure 3 could perhaps have been titled, “A Model of a Generic Firm.” That is, it doesn’t appear specifically to apply to software engineering, or even to engineering in general. This isomorphism is not a coincidence, but more discussion on that will have to wait for a future essay.

In any event, we now have some pieces in place to answer the guiding question of the essay: what are software best practices?

Best Practice 1: Crank the flywheel in Figure 4.

In practice, this means:

1a) Strive to align each edge in Figure 4 with mechanism(s) that are known, documented, understandable, and usable.

1b) Leaders with increasing responsibility should take on broader scope to close and tighten loops in the flywheel.

What comes next

This may all sound a few degrees too abstract. An upcoming Part 2 essay will propose specific processes, mechanisms, products, procedures, principles, tenets, and templates that could be used to bootstrap or accelerate parts of the flywheel that need the most attention.

-

This is a real idea! See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f84n5oFoZBc ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turing_completeness ↩

-

From Jim Collins: https://www.jimcollins.com/concepts/the-flywheel.html. As adapted at Amazon: https://www.samseely.com/posts/the-amazon-flywheel-part-1 ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accelerating_change#Kurzweil’s_Law_of_Accelerating_Returns ↩