Rural Gentrification: A Minifesto

Part 1: Bankrupt Ideas

I graduated from college twelve years ago. Since then, I’ve worked in politics and government and non-profits and corporations, and for organizations on the political “left” and “right” and everywhere inbetween. My first job paid $50 a month (in Brazil) and I’m now at a software mega-corporation. So it’s been a somewhat meandering tour through different slices of life and politics and society.

I want to share some terrible ideas that I’ve collected over the course of my tour.

Why share bad ideas? Well, one thing I think we can all agree on is that in the course of history, terrible ideas have often had massive influence over large groups of people. In the past 200 years, the easiest examples to point to are various flavors of racist ideologies that justified slavery, genocide, mass war, segregation, and imperialism. These were (and are) ideas about “racial superiority” that were based on junk science and junk philosophy at the service of greed and bloodlust. But there are also less abhorrent bad ideas – for example, that left-handedness is a curse to be beaten out of small kids – that large numbers of people believed for a long time and that created senseless harm in our world.

So I think it’s safe to assume that, just like at every other point in history, that there are some really bad ideas floating around, ideas that people will find as stupid as the idea that we need should sacrifice goats to please Zeus for good fortune.

I can’t say that these are the worst ideas, and definitely not the only bad ideas, but these are ideas that seem to be (1) held by a lot of people I’ve met, especially in the college-educated crowd, and (2) really bankrupt at the core.

Bankrupt Idea 1: People should have to work 40 hours a week to afford a good life

I say this because there’s a very common but usually unspoken assumption that our “economy can’t afford” to allow people to work dramatically less than they do today and still have enough money to pay for a good life. This is nonsense.

Here’s how I’d define a “good life.” Safe, sanitary living conditions, free from preventable risks to health and safety. Nutritious meals. Protection from the elements. Opportunities for cultural stimulation, recreation, and exercise. Easy access to trustworthy child care. Local community of friends and family. Engagement in civic life. Protection from arbitrary discrimination and oppression.

The fact is that humans have been working at this for 100,000 years. We know how to provide all these extremely efficiently, if we choose to. There is just no question about this. A good life is not fundamentally expensive.

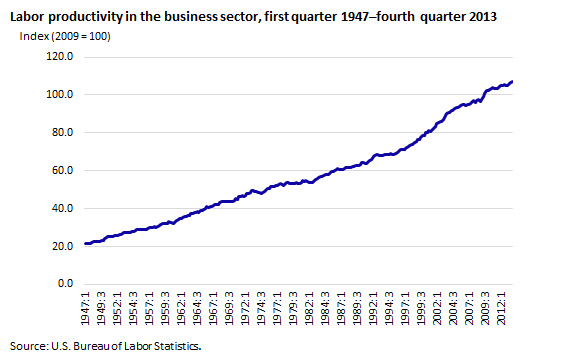

In the United States, productivity has gone up more than threefold since 1960. That means, in very crude terms, that we can produce three times as much stuff – food, energy, housing, clothing – with the same amount of effort. Or put differently, we could enjoy a 1960s-era standard of material wealth, if we wanted to, while working one-third the hours. And it gets better: with the same income, we could still afford a lot of modern stuff. A modern laptop, adjusted for inflation, costs less than a black-and-white tabletop TV did in 19601. A new 2019 Kia Forte – complete with its better fuel-efficiency, safety features, and satellite radio – costs just about the same as a new 1960 Volkswagen, when you adjust for inflation (around $15,000)2. Your internet connection and worldwide free communications would still cost less than the phone bill did back in 1960. You wouldn’t lose those things. They’re all the results of countless ingenious time-saving inventions that are never going to be un-invented.

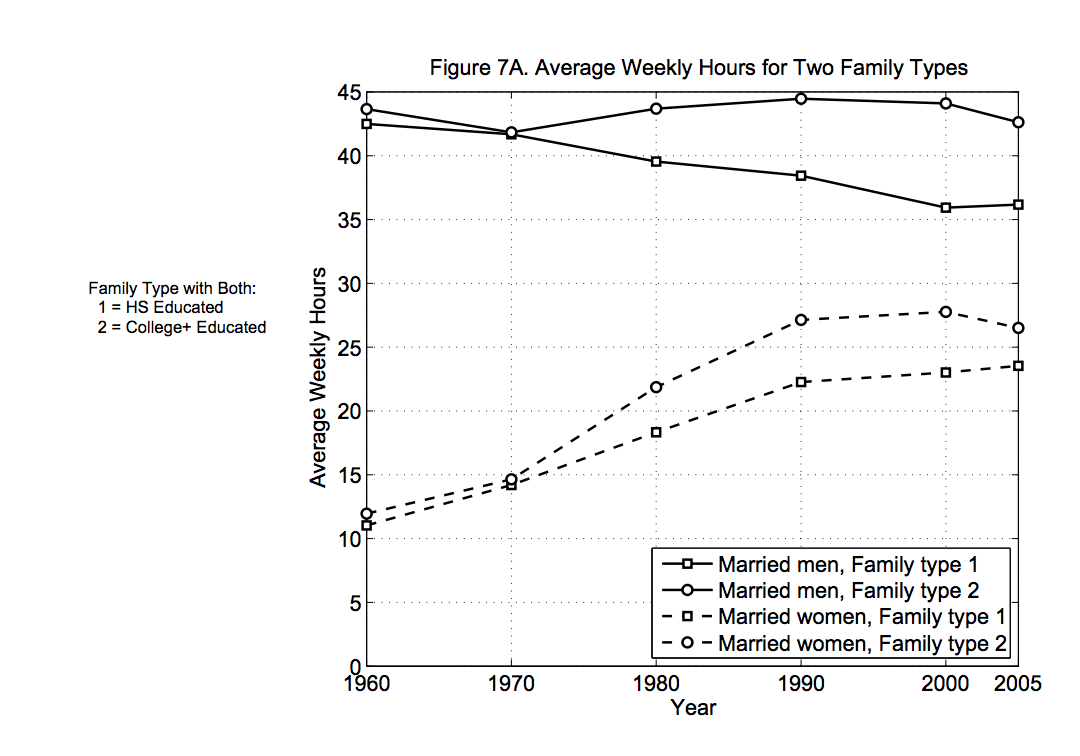

At the same time, we’re working now more than ever, despite the number of people who have left the workforce and lost jobs due to displacement and automation. It’s particularly acute for married families. In 1960, the average hours worked per adult in a married, working-age couple was 25 hours; in 2005, it was 32 hours. This is mostly due to the increased labor participation of women, but also, as we’ll see below, college graduates and salaried workers.3.

We all know people who were alive in 1960. It’s worth asking them whether the material quality of life (put aside politics/segregation/racism/sexism, which were clearly awful but not related to the cost of food or a car) was so bad – so bad that we wouldn’t accept them in return for a single-earner 15-hour workweek that’d pay all the bills for the whole family.

This whole line of argument has been around for a long time. Thomas Paine made the argument in his 1795 pamphlet, Agrarian Justice. The economist John Maynard Keynes famously predicted in 1930 that within a century, the 15-hour workweek would be standard. Peter Kropotkin made roughly the same calculation in 1892. It’s just common sense. Better technics (technology + techniques) produce more stuff with less effort. And the technics always get better.

If people have been making this argument for so long, why hasn’t it gotten much traction? Why isn’t the 15-hour workweek, or perhaps the four-month workyear, the standard?

First, we live in a capitalist economy. Wage workers produce more value than they’re paid, and the excess value goes to the owners of capital. So owners have every reason to want their employees to work as much as possible. And so they’ll lobby and resist furiously to prevent any additional concessions to workers that could impact profitability. When there’s no force of organized workers to counterbalance, the capitalists win. The 40-hour workweek was only won after bitter struggle between organized labor and capitalists, the likes of which we haven’t seen in a very long time.

Second, and this is related, basically all of the productivity gains have accrued to owners of capital. In other words, when better technics are introduced, workers get paid the same, or get fired, and the gains go to right the capitalists. This is no secret.

Third, some things really have gotten a lot more expensive, even adjusting for inflation. Medical care, rent, formal education, and child care have ballooned in the past half-century, much faster than inflation. What’s obvious about these categories is that they’re all services, not products. If we’re paying more money for the same services, we’re getting scammed. In Part 3 I’ll get into some ideas for how to escape from the scam. But suffice it to say, there’s fundamentally a scam behind each of these services, though rent is the king of scams. But while we’re victims of the scam, it is true that the gains of productivity are getting squeezed away in our increased rents and child care and medical bills.

And fourth, corporations have gotten better and better at squeezing more hours out of their salaried workers – who don’t even make more money when they work more hours. Economic research shows that around 1970, salaried employees started working more and more hours, primarily as a result of greater “perceived job insecurity” and corporate bonus, career advancement, and promotion incentives.4

These are all hard facts about the way our society is organized. It is not obvious what we’d need need to do to change the balance of power and wealth and to rearrange ownership in order to work less. I will suggest some first steps in Part 3. But what is blindingly obvious is that we have the skills, the technics, the machines at our disposal in order to free up most of our waking hours for our pursuits of passion, purpose, and community, if we accept an incrementally humbler material existence.

Some people are already “there,” too. There’s a whole “financial independence” community of people (mostly in software and real estate from what I’ve seen) who figured out how to minimize their cost of living and save up money to retire early, sometimes before age 30. They’re also almost without fail highly privileged and college-educated. We can go further.

Technics developed over the generations are part of the shared human heritage of invention and discovery. Everyone willing to work should have an option to earn a decent living for his or her family, with the help of our technical heritage, on 15 hours a week or four months a year of 40-hour weeks.

Bankrupt Idea 2: We Should Hope for Politicians to Solve our Social Problems

“Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.” - US President John F. Kennedy, Inaugural address, January 21, 1961

“America does not want to witness a food fight; they want to know how we’re going to put food on their table.” - US Senator Kamala Harris, Democratic Party Presidential Debate, June 27, 2019

For any large-scale social change, there’s a general sequence of steps. Step One: ideas spread, through conversations, lectures, books, radio, etc. Then, Step Two: civil society institutions – think about universities, newspapers, religious associations, nonprofit groups – explicitly agitate for change at a larger scale. There are all sorts of actions – at the level of individual decisions, family choices, company policies, applying pressure via boycotts and strikes – that don’t require any changes in law. People push for change at these levels, at the scale of our everyday lives. It’s at this level where the “war of ideas” really plays out.

And then finally Step Three: politicians and governments only come in at the very end, in fits and starts, in the messy process of legislation, once the war of ideas has already played out. Legislation isn’t always required, but sometimes it is, and it can easily backfire or have unintended consequences. And the timing is always uncertain, depending on who happens to hold power in which places, and where an issue fits in lots of politicians’ political priorities.

The point is, that legislation and policymaking is the final step in social change, not always a necessary step, and the one which we can influence the least as regular citizens. And so the bankrupt idea is that if we could just elect some great politicians, that our social problems would be solved. Or conversely, that if we have bad politicians in office, that there’s nothing we can do to make progress on fixing them.

The right way to look at this instead, is just to invest a lot more energy and hope in Step One and Step Two: spreading and debating ideas, supporting organizations that will advocate on behalf of good ideas regardless of who happens to be in office, and supporting causes that can be activated outside of the political system. This isn’t a new insight, but there are so many people so wrapped up in presidential politics specifically, that it bears repeating.

Take the issue of gun violence, for example. America clearly has a problem with gun violence. Liberals tend to place the blame on lax gun control laws. Conservatives point to mental health problems that afflict violent individuals. It’s pretty clear that both sides are partially correct. But if you actually care about reducing gun violence, the least effective possible way to do so is to vote for an “anti-gun” or “pro-mental-health” presidential candidate. If your candidate loses, your effort was for naught. If she wins, there’s no guaranteeing she’ll actually be able to pass tighter gun control laws and even less guarantee that she’ll be able to legislate better mental health for the whole country.

But there are so many other ways to make a tangible difference that don’t depend on who happens to win or what laws happen to pass. Donate to a gun control advocacy organization – one that will apply pressure year after year to change laws in all 50 states. Or do your part to address the mental health epidemic. Reach out more to neighbors who seem isolated and withdrawn. Be a part of a religious organization that helps give purpose and community to the most marginalized members of society. Work less, spend less time consuming media, spend more time building relationships.

True, these are all easier said than done (I’d never donated to a gun control organization before I wrote this). So at the very least, if you find yourself caught in the argument that “this is the most important election of our lifetime”, appreciate that that argument only serves politicians and pundits and media companies whose incentives are very different from yours and mine. Political news is fundamentally entertainment and elections are the least effective tool of social change. Don’t get your hopes up that they’ll save our world.

Bankrupt Idea 3: There Are Two Categories of Americans

We live in the era of “mega identity.”5 There are seemingly two categories of Americans: Republican and Democrat. Once you know which bucket someone falls into, you can also reliably predict much more about them. In the book, Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Identity, Liliana Mason wrote, “A single vote can now indicate a person’s partisan preference, as well as his or her religion, race, ethnicity, gender, neighborhood and favorite grocery store.”

In one sense, the facts are indisputable. We have indeed become more predictable. And that means that we’re thinking less and less for ourselves, and accepting more and more the dogma of our cable news channel of choice.

But things don’t have to be this way. And we should be outraged that we are. It’s completely absurd to think that in a complex society of 300 million people, that we can be so easily split into just two categories. If we aren’t thinking for ourselves, if we are so easily predicted, then we are not free. We are something like automatons.

Who’s controlling the automatons? The “mega-identity” trend of course has complex roots. But if we want to understand why things are this way, we just have to ask the classic economic question: who benefits?

Large media companies prefer there to be as few categories as possible: If not one, then two. The few the number of categories, the larger possible audience in each category. The bigger the audience, the more money they can make. Large media companies also prefer people to be predictable: the more predictable, the more certain they can be that a given piece of content will “engage” their audience and earn advertising or subscription money.

Advertisers also prefer people to be predictable. The more predictable, the more effectively they can advertise.

And of course, major political parties prefer this, too. The more predictable their constituents, the easier it is to market to them, to engage them, to craft compelling ads. It’s a lot cheaper to be able to create one TV or internet ad that plays across the country than to have to make totally different ads for different states and counties and constituencies.

But it’s no use to blame media and advertising and political parties. They’re just pursuing their own self-interests in a capitalist society. We, regular people, have to recognize that this whole trend of “mega-identity” is a sad state of affairs. It’s a bankrupt idea that humans are so simplistic, so unfree in our thinking, that there are basically “just two categories.” In Part Two I’ll come back to this with an idea for one way to break out of it.

Bankrupt Idea 4: Cities Are More Interesting Than Towns

There’s a particular category of people, especially fresh college graduates, that gets caught by this bad idea. I was one of them. The general line of thinking goes: big cities have the “most interesting” people, the best restaurants, the richest culture. Therefore, cities are interesting. Let us examine each one of these claims.

Most interesting people. What this really tends to mean is, “the most people like me.” In reality, there’s no way to know what it means to be an “interesting person” and certainly no way to know in advance whether one place has more or fewer of them. We all end up spending time with a small number of colleagues, friends, family, and others with shared interests. Unless you need to have friends who share some really specialized interests – say, Paraguayan cuisine – you’ll find good, friend-worthy people anywhere if you’re willing to talk to people who aren’t just like you.

The best restaurants. This is probably true. But since when are we so elitist that we “must” live where there’s the best fine dining? Since when was it respectable and not snobbish to declare oneself a “foodie”?

The richest culture. By this, people tend to mean something like “more art museums” or “more jazz clubs.” But real culture is participatory – sharing in the process of making art and music. It’s true that cities have the most bountiful opportunities to consume live shows. All other consumer media – music, film, radio, books, newspapers – can of course be consumed from anywhere there’s an internet connection. But what you want is to participate in culture. And in that sense, there’s nothing that makes cities particularly privileged. On the contrary, cities are more professionalized and so they can make it more difficult to participate as an amateur.

So much for the purported benefits of cities. The costs are obvious: they are crowded and they are expensive. You lose your time to traffic and transit and you lose your money to rent. With less time and less money, you have less freedom to craft life according to your own values and dreams. You’re further from the land and from nature.

So here’s the relevant thought experiment: if you could get a good job in a small town, and be guaranteed that there would be 100 trusted friends and family in town, would that make it a more interesting place to live than a nearby city that costs 40% more?

If I’m lucky, I’ve convinced you that it’s a question worth considering seriously.

Bankrupt Idea 5: The American Dream

If cities are too expensive and too congested, what about the suburbs? Aren’t they a logical choice?

No.

The suburbs are not the correct solution to any problem. They’re a way to escape from the problems of the city – crime, congestion, pollution. And they were mostly designed for the benefit of car companies and banks and homebuilders, not for the benefit of real families. They don’t have the intimacy and connection to the land that you find in small towns, but they still don’t have the walkability of city life. Nobody should be proud to live in a suburb. People are there because they’re desperately running away from worse options in the city.

More broadly stated, the whole notion of the American Dream – long-term suburban single-family homeownership – is just a bankrupt idea. It doesn’t make practical sense or financial or moral sense. Plenty of people realize this already but it’s still an undercurrent in the general national consciousness. So let’s just spell it out.

First, owning a home is a poor financial investment. This is no secret. If you have a chunk of cash available for a down payment, there are simply better ways to make that money grow, if that’s your goal. If you invested $100,000 in an average American home in 1975, for example, it’d have grown to about $500,000 in 2013. But if you’d have invested the same amount in the S&P 500, it’d have grown to $1.6 million.6 Another illustration of this fact is that if housing were such a good investment, most homes would be owned by professional investors.

On average, US housing has historically appreciated only slightly above inflation. “Investing in my home” is hardly better than opening a savings account. In reality, the most helpful financial function of homeownership is a psychological trick: paying a mortgage forces people to put away money every month towards their “investment” – even when they could have higher-return investments elsewhere.

Second, the single-family home lifestyle is a colossal sink of time and money. My wife and I moved to the suburbs because we had three very small kids (nine-month-old twins and a two-year-old) and just wanted to make it possible for the kids to get fresh air and be outdoors during the rare Seattle moments when it wasn’t raining. My wife didn’t drive at the time. So we figured that having a yard and a safe, dead-end street would make it easiest to slip outside and run around for a bit when the rain stopped. And because of the Seattle rain, we knew the kids would be indoors a lot, so we thought it’d be better to have more space (than the two-bedroom apartment we were leaving) so everyone could be comfortable indoors, and similarly, have room to jump on a trampoline or do some somersaults or read quietly through the long winter. Just about everything in the city of Seattle was out of our price range.

But what we didn’t appreciate were all the costs of living in a bigger home in a less dense neighborhood. Everything around the house took twice as long. Longer to find the kids around the house! Longer to corral them to the dining room for a meal. Longer to walk between the kitchen and dining room to serve a meal. More bathrooms and floors and windows to keep clean. And not to mention the yard maintenance, which has actually taken years to figure out. Or the one-hour commute to work each way. Death of our “down time” by a thousand cuts.

Third, single-family homes are lonely traps for kids and adults. Single-family-homes are the least dense residential type. That means, by definition, that it allows the fewest possible people within walking distance or biking distance. It’s the loneliest way to live.

It’s even worse when cars dominate the streets. In our neighborhood, for example, there are no sidewalks. So our kids – aged 5, 5, and 6 as of this writing – cannot go anywhere outside of our little cul-de-sac without an adult to escort or drive them. And it’s not because we don’t trust the kids to be out of sight. When we travel to campgrounds, fairgrounds, or farming communities, the kids get free reign on their bikes. But back in our neighborhood, the car traffic just makes it too dangerous for them to roam, at least at this age.

And we see what happens as the neighborhood kids get older. Even when they’re old enough to bike around and contend with cars on the street, there’s nowhere to go. The kids are too spread out, and besides, kids don’t roam the streets and parks anymore (We’re all familiar with this trend, apparently triggered by highly-publicized child murders and kidnappings in the 1980s). And so parents, guilted by the lonely traps of their neighborhoods, become semi-professional chauffeurs, shuttling their teenage kids between organized social activities. It’s a trade of one kind of loneliness for another.

But the same dynamics are at play for the adults, too. There’s no escaping the fact that people are just harder to find when they’re more spread out.

Fourth, homeownership makes people greedy. Owning a home makes people greedy in two ways. The first way is that when people are bought into the idea that their home is an investment, they’ll naturally do everything they can to make the value of the investment go up. And the most obvious way they do that is by keeping other people out of their neighborhood in order to make it more exclusive, to preserve their views, and therefore make their own property more valuable. So they oppose efforts to allow more housing to be built in the neighborhood to respond to population growth. This has happened all over the place in Seattle, a city that considers itself to be otherwise liberal and inclusive.7 The effect is that it makes rents and property more expensive, making life worse for everyone who isn’t a homeowner.

The second way that it makes people greedy – and this is the more tragic effect – is that it encourages them to become emotionally attached to their property, even when it’s not growing in value. There’s very well-understood psychological mechanism called cognitive dissonance at play. When someone makes a huge commitment, like buying a home, their mind immediately starts to invent reasons why it was a great decision. It may start with “this is a great financial investment” but then, after the years, it turns to, “I am in love with my home.” This is how one Chicago condo owner described her attachment to her home, when a nearby school was considering buying the building in order to serve more students:

“Our condo is not merely ‘contiguous property,’ as Parker’s board chair and principal put it. It is our home. It is the childhood home of our now 20-year-old daughter — the home in which she grew up. It is our forever home.”

What’s wrong with loving your home too much? It’s the same thing that’s wrong about my son getting so attached to a Lego toy that he refuses to share it with his brother even when he’s not using it. Being too emotionally attached to property often prevents the owner from putting it to the best social use. It creates the delusional attitude of the Chicago condo owner – that moving from her home would somehow erase her daughter’s childhood memories.

Escaping the Trap

But you can’t have it all, right? If you want more green space, you better be willing to maintain it, and you have to accept that the neighborhood is going to be less dense. If you want a bigger home for the same price, you have to accept a longer commute. These are the facts of life.

That’s what most of us suburban dwellers tell ourselves, begrudgingly. For lack of a better alternative, we come to love our useless little home gardens, take pride in our shiny power tools, and retreat permanently into domestic suburbia, content to delude ourselves that we’re “making a responsible investment.”

But I think we can have it all. We’re locked into a set of out-of-date designs and tradeoffs. We just have to take back our time and get way out of town.

Interlude: Maybe the most important fact about American life

Before I move on, there’s one other fact about American life that I have to point out. It’s one of those things that I think helps you understand everything else.

And that’s that according to Nielsen, American adults now spend, on average, between 10 and 11 hours every day watching, listening to, or reading media content on their TVs, computers, radios, tablets, consoles, and smartphones.8

To be clear, time interacting with multiple media simultaneously counts double. So an hour watching TV while browsing social media counts as two total hours. But still. This is a mind-boggling amount of time. This does not include reading books or newspapers, or even making phone calls or writing social media messages. This is 10 to 11 hours of consumption, 365 days a year. Just let that sink in. I’ll come back to it later.

Part 2: Gentrifying the Countryside

In the last section, I attempted to expose the bad ideas and trends that have gotten too many modern American families into a particular kind of mess: squeezed for time and money when there is more of both than ever to go around, losing every spare moment to an epic digital media addiction, duped into believing that overpriced cities are interesting, sold a bad investment in the lonely, wasteful, time-sucking suburbs, hoping for politicians to produce solutions that politicians can’t produce alone.

This is not to say that things are worse now than they ever have been, or that life is fundamentally miserable. On the contrary. But still, every generation has its own problems, its own bad ideas to exhume, and they don’t discount all the wonderful things happening simultaneously in the world. These are just the problems for our time, the problems I’ve felt firsthand – and I’ve been lucky to have skirted the worst of it.

How do we untangle ourselves? I don’t know. But here are my best ideas.

Civic Solidarity

I like to stop and think every once in a while about every human that made my day possible. The miners who dug out the aluminum for my computer. The mothers and wives who fed those miners. The tanker captains who brought the garlic in my lunch from halfway across the globe. The construction workers who built my house. The countless farmers around the globe who made my food possible. The lawyers and bankers who supported the farms. The computer programmers who struggled through crashes and errors to make my devices seem so magical. The native people forcibly displaced my family could eventually own the land. The day care teacher who looked after the kids so the painters could paint. And on and on.

It’s mind-boggling if you get into it. The worldwide collaborative dance of trade.

Who’s running the show? Who makes it all work? Of course, there’s no single entity. But it’s not done on the honor system or by charity either. Obviously, it’s mostly private companies, who operate on the money system, and whose success depends on earning more of it than they spend.

And so, even though companies are often competing with each other, they generally share a few goals. First, they would like for economy to grow. They would like for people to work as much as possible and to spend as much time and money as possible consuming things, including consuming bad things, like addictive drugs or heart-bypass surgeries. And second, they would like for people to be predictable. That makes it a lot easier for companies to plan ahead.

Economic growth can be a wonderful thing, and so can consumption. The problem is that “the economy” does not distinguish between good and bad types of growth, or productive or destructive kinds of consumption. It doesn’t distinguish between “predictably happy” or “predictably racist.” The economy is bulldozing forward, pursuing growth and predictability at all costs, with the force of most of the world’s working people behind it.

And it’s in that light that I view the bankrupt ideas and troubling trends from Part 1. They’re all symptoms, in one way another, of bad growth. They’re ways in which the economy has managed to create pockets of profit by selling faulty ideas.

So how do we change the economy?

I submit that we must start with civic solidarity: as volunteer citizens, organizing outside of the self-sustaining power centers in corporations and electoral politics and the nonprofits they bankroll. The reason is this. If you’re in the corporate world, profit and growth and predictability will always outweigh doing the right thing. If you’re in a salaried job at a non-profit or government agency or company with an important social mission, that’s great (I’ve been there), but you’re quite constrained in voicing your honest opinions, for fear of professional consequences. If your livelihood depends on it, you can’t help but prioritize your institution’s values over your conscience. Or even worse, you ignore the difference between the two. I saw this tragic effect firsthand when my idealistic peers from the Obama campaign went to work in Washington.

The point is that voluntary civic associations are really the only kind of institutions powered by common pursuit of a higher ideal. In the past, these took the form of religious groups, trade unions, neighborhood associations, professional associations, and charities. These all still exist is weaker forms today, but there are also new, modern forms too. Reddit and WhatsApp and Facebook communities are now the leading edge of civic society, and where much of the war of ideas is fought and won. This once was common knowledge, but it seems to have been lost on many of us. Civic society is the primary vehicle of social change.

And we must organize. The corporate world is massively well-organized; consider the dance of global trade I marveled at above, coordinated by billions of people, millions of organizations large and small, trillions of dollars of capital, all in the pursuit of more production and more consumption.

Who’s going to stand in the face of the mega-machine of our economy and ask it to slow down, to be more cautious, to give us more time to tend to our families and neighborhoods, to reward sharing and thrift, to cure our loneliness, to orient itself towards long-term sustainability and well-being?

Does anybody really trust the Democratic Party or the Republican Party to do that work? Does anybody really believe that any US President — no matter how competent — can fix all this on her own? No, civic society is where that work happens.

As individuals, we are powerless in the face of these organized forces of economy. Our votes, our consumer decisions, no matter how righteous and well-considered, are useless if we have no independent apparatus for coordinating our actions. Otherwise we are steamrolled by the forces — and the trillions of dollars behind them — that are coordinated. Namely, the corporate world.

That’s not so say that the corporate world is necessarily an enemy to be defeated, or that its interests have nothing to do with ours. It’s fabulously good at giving us what we want, when what we want is very clearly and unambiguously defined. But it has certain points where its interests do diverge from ours. Where we have to step in and put it in its place. Where we have to send a more forceful message about what it is that we actually want and don’t want.

This is where reasonable people will say, “And that is what government is for! It’s for putting guardrails on the private sector. That’s why we have regulators and watchdogs and anti-trust.” But one thing I didn’t appreciate when I entered the political world as a young Obama organizer is that government policy is the last and often unnecessary phase of social change. Before policies change and politicians are elected come years of work building political power around ideas and causes. This is where the most important work in social change happens. This is the space inhabited by Gandhi and MLK Jr. This point will seem terribly obvious to anybody who’s done even a little activism, but it just bears repeating because too many people spend too much time focused on politicians and elections. And too many smart people believe that changing laws and rules is actually the most important (or even only) vehicle of social progress.

Plugging In

The argument from the previous section is that if we’re ever going to untangle ourselves from the current predicaments of our family life, our cities, and our economy, that we have to start with voluntary association and civic solidarity, rather than waiting for politics and politicians.

Now I want to offer some ideas on where to get started.

First, there are existing organizations and institutions: non-profit causes of all kinds, religious organizations, social justice organizations, unions, community associations. When we find one of these that genuinely aligns with our interests, we should offer our time and money to these institutions. We just have to be careful about other people’s agendas: especially, paid employees who want to keep their jobs and get promoted, and rich donors and philanthropies who control non-profits for their own purposes. Some non-profits (i.e. the Republican National Committee) are fully corrupted by those agendas, whereas others (your local elementary school’s PTA, for example) much less so. It’s key to have a radar for that. Once that’s cleared, though, supporting one of these organizations is the easiest way to plug into civic life.

Second, there are online communities. The great strength and weakness of these is that they’re generally all-volunteer. In these — Facebook and Reddit and Twitter communities are the clearest examples — it’s easier to build passion and enthusiasm (since everybody who’s there actually wants to be there) but it’s harder to coordinate. But still, some norms and guidelines and common themes emerge over time, and these online communities can turn into institutions of their own. The primary science news community on Reddit (“/r/science”), for example, is perhaps the world’s most viewed source of science news and commentary, with more than 20 million subscribers. A single post on a Reddit politics community was the genesis of the 2017 March for Science that included over 1 million demonstrators around the world on Earth Day. These are powerful and impactful communities — and in many ways, more effective than traditional activist networks.

And third, there are our organic communities of friends and family. We often don’t think of our family, for example, as an “institution,” but it absolutely is one — if often less effective and less functional than it should be. Just like non-profits and insurance companies have their own mission statements, every family unit has a mission, too: to provide personal support, security, meaning, companionship and safety to all of its members. And I’d argue that investing in one’s own family institution(s) — however big or small, however the boundaries are drawn, regardless of blood relation — is probably the most valuable way to build civic solidarity. Having a strong family institution is the best insurance plan against economic turbulence, against the loneliness epidemic, against political uncertainty. And it’s got the tremendous advantage of built-in trust relations, making it much easier to communicate and solve problems and work past personal differences compared to faceless online communities or distant non-profits.

(That’s not in any way saying that personal problems — major ones — don’t exist within families. That would be the least true statement of all time. But the fact is that parts of the family that really can’t stand each other naturally splinter apart, leaving segments composed of people who genuinely do trust and care about each other much more than they care about strangers. Each inner core — people who share high trust — is what I’d consider its own “family institution.” And it’s that unit that should be cultivated and strengthened and even expanded as new relations come into the picture.)

“But,” some will say, “I’m not close with my family and don’t think it’s worth it to get closer.” I get that — there are so many valid reasons to get to that point, though I do think it’s a tragic place to get to, since it means that parents somewhere have failed.

Still, if your most important trust relations are elsewhere — friends, colleagues, associates — then perhaps those relations the starting point for your real family institution, and you should cultivate that instead.

What does it mean to cultivate the family institution? Don’t we do that naturally in our relations with loved ones?

Here’s what my extended family does (and this includes one divorced couple and all variations of step-siblings and step-parents):

- We have monthly scheduled videoconferences with rotating call leaders to share reflections, news, and discuss family business.

- We have paid and free software accounts for calendars, group communication, document storage, and project management.

- We collect money from members to pay for our shared accounts and software.

- We are organizing a family reunion.

- We send money to extended family members in need.

These are the kind of things that take just a bit more effort and money than the kind of informal organizing that we used to do before we introduced the idea of the family as its own institution. It was really just a mental shift — realizing that we always operate as an organization, whether we like it or not, so we might as well run it deliberately.

Issue-oriented non-profits, online communities, organic friend-and-family networks — these are the wellsprings of focused and sustained social change in our world today. I’ve come to appreciate that it’s far more worthwhile to build these institutions than to gossip about national politicians and governments, or to read or watch the news entertainment, which all accomplishes nothing or worse.

Taking Back Our Time

Invigorating our civic life may sound great. But who’s got time for that?

As I wrote in Part One, college-educated families are working way too many hours. It’s not necessary and it’s not healthy. Higher-paid men have been working more and more hours since the 1970s, and college-educated women work drastically more than they have historically. So for the average household with two college-educated partners and one or more kids, there’s hardly time left for anything else besides work and parenting and domestic duties.

College-educated people, but in particular salaried employees, just have to organize to bring down our working hours to a reasonable level. This should start with large institutions and corporations that can afford to do this right away; salaried employees should just sign a pledge that they’re going to work 1970s-era hours (averaged across men and women) and devote our newfound time to service civic causes to help our world avoid political and environmental meltdown.

People without a college degree aren’t getting paid well enough, and so I think their concern is money and not time.

And then for all of us, we have to confront the media consumption statistics I wrote above. The 10-11 hours a day we spend consuming media. We can blame the media companies and advertisers for creating addictive content, but we can only blame ourselves for consuming it.

It’s not that all media are bad. But most TV and social media and video games are bad. They’re bad because they’re fundamentally about escapism, about dealing with life’s by problems by visiting other worlds or lives whey they don’t exist. News is especially bad because it gives us the illusion that we’re doing something “important” when it’s just providing a form of gossip. But some social media is phenomenal, and helps great ideas spread and people organize in ways they’ve never been able to.

In any event, we just have to be more intentional about media. We should all have a “philosophy” about what media and how much is healthy. And we should publish our personal consumption stats and content as a way to hold ourselves accountable. We should be appalled by ads that describe TV shows as “binge-worthy.” And we should aggressively cultivate our social media so that our media diet matches up with our philosophy.

Otherwise, the media companies have a stranglehold on our precious attention and they’ll use it for their own purposes. And serving voluntary civic associations is just about dead last on their priority list.

And finally, we have to find social safety net mechanisms to make it easier to stop working for longer periods of time. I’m one of a tiny number of people who has (1) enough savings and (2) and employer who’ll allow a 12-week unpaid leave from work. It’s been tremendously regenerative and positive for my family. And I never would have written anything without it. But there are so many better writers than me, with more interesting things to say, who’ll never get the chance. And so many new parents who are over-worked and over-stressed who’d benefit even more than me from a break, to attend to their kids and their families and their neighborhoods. However we do it — government entitlements, credit unions, direct wealth transfers — the point is that we have to make it a lot easier to take a lot more time off. It’s not like we’re going to run out of food if we do. I don’t know how exactly we get there. But the first step is we all agree with the general idea.

The New Exploration

The other way to take back our time is to reduce our costs of living. The lower our monthly expenses, the earlier we can retire or take a 12-week unpaid break from work. And the great thing about this approach is that it’s totally under our control and not dependent on a government entitlement or a raise from our employer.

Housing is our biggest expense, so that’s the best place to start reducing cost of living. And the most foolproof ways to do reduce housing costs are to (1) live more densely, and (2) get far away from the expensive city centers.

Here’s where I want to paint a picture of what such change might look like, especially for liberal suburbanites like me. It’s also where I want to get back to Bankrupt Idea 3 (“Cities are more interesting than towns”), Bankrupt Idea 4 (“There are two categories of Americans”), and Bankrupt Idea 5 (“The American Dream”). If I’ve convinced you that those are, in fact, bad ideas, the path to sanity perhaps inescapably points to a movement from cities to rural America, or to put it provocatively, Rural Gentrification.

For inspiration, here’s an except from The New Exploration, written by Benton MacKaye, the visionary behind America’s treasured Appalachian Trail, from 1928:

Here is a significant and decisive question for this generation. Can we make of this time and century something better than a chaos of industrial cross-purposes? We find ourselves in a the shoes of our forefathers: their job was to unravel the wilderness of nature; ours is to unfold the wilderness of civilization. Or are we to be lost in the jungle of industrialism? Are the elements of water and steam and fire to remain our masters, or will they become our “servants for noble ends”? Are we going to ride on the railroad or let it ride on us?

The forces set loose in the jungle of our present civilization may prove more fierce than any beasts found in the jungle of the continents — far more terrible than any storms encountered within uncharted seas. Here in America — particularly in Appalachian America — we have an area which, potentially, is perhaps the most “volcanic” of any area on earth. It is an area laden with the ingredients of modern industry and civilization: iron, coal, timber, petroleum. It is electric with a high potential — for human happiness or human misery. The coal and iron pockets which lie beneath the surface may be the seeds of freedom or seeds of bitterness; for in them is the latest substance of distant foreign wars as well as deep domestic strife.

These forces are neither “good” nor “bad” but so. And they do not stand still, but flow and spread as we have told. Can we control their flow before it controls us? Can we do it soon enough? This is a crucial question of our day. What instructions can we issue to our modern-day explorer (whether technician or amateur) to guide him in coping with this modern-day invasion?

The new explorer, of this “volcanic” country of America, must first of all be fit for all-round action: he must combine the engineer, the artist, and the military general. It is not for him to “make the country,” but it is for him to know the country and the trenchant flows that are taking place upon it. He must not scheme, he must reveal: he must reveal so well the possibilities of A, B, C, and D that when E happens he can handle it. His job is not to wage war — nor stress an argument: it is to “wage” a determined visualization. His attitude is this must be one not of frozen dogma or irritated tension, but of gentle and reposeful power: he must speak softly but carry a big map. He need not be a crank, he may not be a hero, but he must be a scout. His place is on the frontier — within life’s “cambium layer” — the fluid twilight zone of all creative action in which the flickering thoughts of future are woven in the structure of the past. … And our last instruction to our new explorer and frontiersman is to hold ever in sight his final goal — to reveal within our innate country, despite the fogs and chaos of cacophonous mechanization, a land in which to live — a symphonious environment of melody and mystery in which, throughout all ages, we shall “learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids,” but by that “infinite expectation of the dawn” which faces the horizon of an ever-widening vision.

When those words were written, nearly a century ago, the author criticized America’s cities as too big, too crowded, too expensive, too hostile to our human needs.

In place of a world, there is a city, a point, in which the whole of life of broad regions is collecting while the rest dries up. In place of a type-true people, born of and grown on the soil, there is a new sort of nomad, cohering unstably in fluid masses, the parasitical city-dweller, traditionless, utterly matter-of-fact, religionless, clever, unfruitful, deeply contemptuous of the countrymen. … This is a very great stride toward the inorganic, toward the end. …

And MacKaye was well tuned-in to the sprawling lifelessness of the suburbs — and this was well before the midcentury explosion of suburban development and “white flight” that we associate with the 1960s and 1970s:

Not content in making small town into a large town; in developing merely a larger community — a unit of humanity within its natural borders and confines: not content in making a city, we make a super-city. We handle the advancing flow of population toward the urban centers just as a mentally deficient engineer would handle the advancing flow of water down the valley. First we build a “dam.” This consists of office buildings where jobs are to be had. The population must reach these office buildings in order to make a living. Then we allow the flood of folks to back up against this “dam” of office buildings until is backs far outside the confines of an integrated city and spills over on adjoining areas. This it does in a shapeless widening deluge of headless suburban massings which know no bounds or social structure.

What we call the “suburban” (the under-city) is really “super-urban” (the over-city — the outer layers of the tide which overwhelms the city). Since there is usually no sharp line between suburbs and the city proper, we have, in such centers as New York, Chicago, Detroit, and other “Greater” cities, in truth no city at all. Instead we have what Mr. W. J. Wilgus of the New York Central Lines has graphically called a “massing of humanity.”

He contrasts the lack of social structure in the suburbs with his experience growing up in a New England village not yet taken over by the “metropolitan invasion”:

There was the swimming-hole in the mill stream — and the flooding of the meadow for skating around the evening bonfire. There was the “after haying” picnic on the river intervals — and the “double-runner” coasting parties by February moonlight. There was baseball — and there was shinny: rainy-day pout fishing — and tracking rabbits. There was the mud scow on the spring meadow — and there was fishing through the ice. There was the illustrated lecture — on the planetary bodies or the Norman Conquest. There was Evangeline read aloud on a long solstice evening. There were May baskets on twilight doorsteps, with loud knockings and merry routs for conquest; there was “drop the handkerchief” on the Common. There was the midsummer authors’ carnival. There was the strawberry festival on the green and the corn-husking on the barn floor. There was the farmers’ supper and the ladies’ autumn fair. (There were quadrilles and reels and slides.) There was the Grand Masquerade in the January thaw. The church bell rang out on the night before the Fourth, as the sleigh bells did on the night before Christmas.

This array of colonial cultural activity is not given in order to picture an ideal. Nor is it a dream of village life in eighteenth-century New England. In every one — and more — of the customs cited, I have myself taken part personally since the 1880’s.

Why the extensive quotes from a book that’s almost a century old?

MacKaye reminds us that the congested city and the soulless suburb and the car-dominated exurb aren’t actually our only choices. America, but especially colonial America, was once filled with country villages — small, walkable, friendly to children, not dependent on cars, socially coherent, in tune with the organic world.

I submit that it’s time to bring that back. But with all the conveniences and inventions of modern technology.

The Modern Country Town

There’s just no getting around the fact that city centers are getting less and less affordable. The same story is playing out in New York, San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago, Austin, Denver, Portland, Los Angeles, Houston. More people are moving in and not enough housing is being built. Traffic is getting worse. Commutes are longer. Our time and money are being siphoned off to rents and mortgage interest and traffic.

There are ways to improve the situation. More housing, more density, and better mass transit are all desperately needed. But the entrenched interests — the “real estate state”, landlords, longtime residents, in particular — have all the power. Big infrastructure projects are more expensive, more difficult, and more disruptive than ever. Our big cities are saturated. We will probably have to wait until a large number of middle-aged homeowners die off before we can speed things up. And even then, there’s no knowing whether their heirs will be more willing to embrace density and change.

At the same time, land in rural America is cheap and wide open for development, and more and more jobs can be done anywhere there’s an internet connection. In 2016, more than 8% of all workers in the U.S. were “fully remote.” 9

Moreover, anybody who’s paying any attention to our climate and sustainability problems understands that we have to find new ways to live within our ecological means. Reducing carbon emission is just one part of the puzzle. We also have to find ways to manage our water, our forests, our plastics, our biodiversity, our waste. Inevitably that’s going to involve changing every aspect of the way we live: how we shop, how we share, how we feed and house and clothe ourselves, how we vacation, how we raise our children.

Where are the frontierswomen of the modern sustainable lifestyle going to come from? Is this dramatic shift in our way of life really going to be led by the federal government, or state governments, or city councils that can’t figure out how to provide beds for people sleeping on the streets in record numbers? It seems just far more likely that the action is going to happen somewhere else, where the numbers are smaller, the stakes are lower, and small groups of like-minded individuals can move much more quickly without enormous entrenched interests to battle.

In sum, the conditions are ripe for a rural revival, led by online workers and the new frontierspeople of sustainable living.

It’s not terribly hard to imagine what this project would look like: take the old model of the colonial New England town and update it with modern technology and values.

Homes are close enough together — think small cottages, row houses, and townhouses — that towns are walkable for children and adults alike. Multi-family housing is the norm, making it easier for grandparents and extended family and close friends to live in close vicinity, so child care is less of a hassle and kids are freer to roam. Cars are second-class citizens in the town centers, so it’s safe the children to get around on their own. Perhaps there are speed-limited electric vans around dedicated alleys to move the larger freight. There’s a modern equivalent of the Town Common — public space for gathering, strolling, conversation, interchange and recreation. The rural resources are managed by the town, so you can perhaps get a town solar farm on the outskirts and a public farm for producing the kinds of produce that really makes sense to be done locally, like greens and fruits. With the magic of e-commerce and the internet, the world’s infinite selection of goods and cultural products are all still just a click away. The cost of land is a fraction of what it costs in the nearest metropolis.

What about the church? The old New England towns were bound by their religious faith more than perhaps anything else. Well, I think something like a “church of sustainability” will take its place — along with its own set of institutions and physical monuments and rituals and instruction. The challenge of remaking our civilization in harmony with the natural world, and that will be adaptable and resilient in the face of a more unpredictable climate — is as great and profound as any that humanity has ever faced. And so I think it’ll take a sacred commitment and religious devotion, too. Part of the genius of starting new rural villages is that the population self-selects, so you can be sure that everybody gets the new religion.

How could such a project get off the ground?

It’s just a series of steps. The first one is for enough people to declare that it’s something they’re interested in doing. Then you have to find a starting point. It doesn’t have to be as dramatic as the epic Mormon journey for their promised land in Utah. One way is to start with an affordable plot in or adjacent to an existing town and highway, where some of the big infrastructure (power and water) are already available. Another entry point is to start as a seasonal or temporary “retreat center” for online workers — where they can go for six months or a year to enjoy good weather and low rent. It could turn into a more permanent settlement over time. And finally, there’s a lot of energy and ingenuity happening at the big summer festivals. Every Labor Day, for example, 65,000 souls create a zero-waste city from scratch for the Burning Man festival. Starting a humble village of 5,000 is only a fraction of that effort.

To be sure, such a project is probably more appealing to someone like me — a new parent, with established friends and family to bring along, thinking about kids — and perhaps less so to a young bachelorette who might be more interested in meeting new people or exploring new social spaces. A small village is certainly more intimate, so you’d have to be pretty sure that you’re going to have good friends or family in town.

The Mass Mobilization

A lot of people I know under the age of 40 expect there to be a major mass mobilization in our lifetimes. It’s often compared to the mobilization during the Second World War: a time when consumers and industry agree to certain shared goals, to extra coordination, and to make shared sacrifices in pursuit of a higher civic goal. Instead of fighting another nation-state, though, this time around it’ll be a fight for the survival of modern civilization in the face of environmental and humanitarian catastrophes.

There are “reactive” and “proactive” versions of the story. The “reactive” version is in response to some very acute disaster: economic collapse, agricultural failure, humanitarian crisis, outbreak of an uncontrollable pathogen or technology gone haywire. The “proactive” version is an attempt to mobilize before the worst disaster hits. It’s more effective (since it theoretically prevents the worst of the damage) but it’s also harder to pull off, since people have to be convinced of a threat before it strikes.

If you feel that a mass mobilization is likely — based on your assessment of likelihood of environmental and humanitarian disaster — then I think you’ll prefer for the “proactive” scenario to happen. It’s got less violence, less vengeance, less panic, more time for people to strategize and behave rationally.

How do you make the “proactive” scenario more likely? By waiting for a government solution? I think that helping to found a sustainable new village — learning how to literally mobilize your friends and family — is a pretty decent place to start.

It will take a long time. City founders never live to see all their work come to fruition. But as the Greeks said, “A wise man is one who plants trees whose shade he won’t live enough to enjoy.” Besides, the overwhelming scientific consensus is that death is a useful but man-made concept that isn’t defined anywhere in the laws of physics. The great projects that outlive our human bodies are literally just as “alive” as our bodies are. We should nurture them.

References:

-

https://www.gobankingrates.com/saving-money/car/heres-much-car-today-would-cost-year-were-born/#12 ↩

-

https://pressblog.uchicago.edu/2018/05/04/lilliana-mason-and-the-age-of-mega-identity-politics-on-the-ezra-klein-show.html ↩

-

https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/052015/which-has-performed-better-historically-stock-market-or-real-estate.asp ↩

-

https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/capitol-hill-homeowners-say-upzone-would-mar-their-views-of-lake-union/ ↩

-

https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.mediapost.com/uploads/Nielsen_-_Q22018NielsenTotalAudienceReport.pdf ↩