Five Intellectual Horrors of the SBF/EA complex

Inspiration for this post:

Automatically downgrading every single thing SBF believed in is an error. It's important to actually think and figure out which things contributed to the fraud and which things didn't.

— vitalik.eth (@VitalikButerin) November 15, 2022

Don't be the guy who would have tried to cancel vegetarianism in 1945.

(My obtuse brain needed to be reminded that he’s referencing the fact that Hitler was a vegetarian).

So. Here’s my catalog of some of the bad ideas I’ve found lurking around in the SBF and Effective Altruism universe. I’m not going to make a claim about causal direction – which came first, the idea or the fraud – because I think they were commingled. The ideas enabled the SBF story, and the SBF story amplified the ideas. In any event, I hope we can use this moment to permanently exorcise these intellectual horrors.

I’m intentionally using strong language commensurate with the scale of damage that was done.

Horror 1: Hard Consequentialism

There’s a sort of folk interpretation of consequentialism that goes like this:

Try to do the most good for the most people.

That’s fine. I mean, who would possibly argue with that? It’s so inane as to be pretty much useless. Or if useful, perhaps as one folk aphorism in a collection of many others. Or perhaps cast as the virtue of compassion.

But I’m taking claim against the SBF/EA interpretation of consequentialism. Let’s call it hard consequentialism. It goes something like this:

You can quantify the amount of good that you create in the world. You have a moral obligation to maximize that number. This is your primary moral compass. All decisions (but especially the important ones) should be put through the following equation: multiply the amount of good any action will create times the probability that the action will succeed. This is the Expected Value of the action. Your goal is to constantly search for actions with the highest Expected Value.

Here’s how SBF described his decision-making after leaving Wall Street1.

Sam Bankman-Fried: This is looking at 2017, when I left Jane Street. Again, I don’t want to portray this as being more confident than it was, because it wasn’t super confident — this is all me just trying to make the best decisions I could, given incomplete information. But basically I just got out a piece of paper and forced myself for the first time in three and a half years — basically the first time since I joined Jane Street — to think quantitatively and moderately carefully about what I could do with my life. I just got out a piece of paper and wrote down what are the 10 things that seem most compelling to me right now, and evaluate the Expected Value of each of them, just ballpark it.

(I think it is clear from the context elsewhere in the interview that when he says “expected value” he means utility – creating good in the world – and not financial earnings. But in any event, this point stands on its own.)

Now, to state a non-controversial point:

It is patently impossible to quantify the amount of good you create in the world or to even “ballpark it.”

It doesn’t mean that you can’t create goodness. You just can’t quantify it. Nobody has a Utility Created Score.

Not to mention that you definitely can’t quantify the second and third and nth order effects of your actions on “total goodness.” Say you donate a kidney to save a stranger’s life, and that stranger ends up having a grandchild who’s a white collar criminal. Do you lose points in the Utility Game because of your donation? There are endless thought experiments like this happening at this very moment among Philosophy 101 college students.

I find it helpful to compare this dilemma to Hayek’s Knowledge Problem. Just like it’s too hard to centrally plan an economy due to the explosion of agents and preferences and possibilities, it’s impossible to centrally account for utility in practice.

In practice, that means it’s delusional to make any actual decision on a purely consequentialist basis. You simply Can Never Know How One Action Will Impact The Sum of Happiness in the World. Period.

So, what do you do? You try to do your best. You listen to your conscience. You try to think clearly. You compare to other situations. You put yourself in other people’s shoes. You draw from something you’ve read. But there sure as hell isn’t a formula.

Because while we know that you can’t possibly sum up the Utility Impact of your actions, we do know that honesty is good. We do know that being pro-social is good. We do know that solving widely-accepted problems is good. We know that seeing past our own biases and delusions (and especially our childish egotism) is good. In game-theoretic terms, we know that cooperation is good. We know that diversity is generally healthy and monoculture is often not. We know that defaulting to non-violence and de-escalation are good (in the same game-theoretic sense; they help us cooperate). We know that long-termist values are good. We know that invention and discovery are good. We know that encouraging these same virtues in our children and in future generations is good.

It’s hard to live by those virtues. It’s really hard. Learning to be honest and to see past delusions is extremely hard. It takes discipline and practice and guidance. There are exceptions and paradoxes. But we try to wrestle with them. This is the work of leading a moral life. This is what I teach as a parent.

On the other hand, hard consequentialism is the very best philosophical foundation for the most abhorrent behavior.

SBF is admirably honest about being a Machiavellian:2

But his whole career path was totally justified by consequentialism. He had a formula in place, and it involved maximixing utility by getting rich and donating. Virtues played no role. He was a consequentialist to his bones. He made wrong estimates about whether he could get away with fraud, but hard consequentialism totally permits committing fraud if you can get away with it.

Now, Sam Harris (and surely others) make the point that his whole downfall has proven that he was a bad person on consequentalist grounds – he has clearly created a lot of negative utility in the world.3 That’s true.

But here’s what they miss, I think: consequentialism is bad on consequentialist grounds.

Or in other words:

The consequence of consequentialism is to encourage antisocial “ends justify the means” behavior.

Just to repeat myself, the ends are impossible to know, and so this kind of behavior (even when well-intentioned) is by definition delusional. All you have to do is convince yourself that your end goal has high utility. Then any kind of awful behavior in its service is justified.

Whereas the consequences of virtue ethics involve every kind of good, pro-social behavior that we want. By definition.

Horror 2: “Strive to Maximize Your Impact”

This is related to Horror 1 but often lives on its own, outside of consequentialism.

When he appeared on the 80,000 hours podcast (which is explicitly part of the Effective Altruism world), SBF constantly used the words “maximizing impact”.1 This was taken by the host as table stakes. I mean, of course people want to have the maximum impact they can on the world. Right?

No.

When I hear “I want to have maximum impact,” what I really hear is “I want to acquire and wield maximum power.” These two statements are semantically equivalent.

It’s the same thing as when somebody says “I want to change the world”. They really are saying that they want to acquire power. Which is by my standards, a pretty terrible goal in life to have.

We should kindly cancel this kind of speech.

We need to encourage people to want to be humble and creative and honest and clear-headed and conscientious and all the other virtues. We should never encourage people to want to be powerful.

Strive for virtue; steward power. Something like that.

Horror 3: The Giving Pledge and others like it

Before we get in to this, I do want to be clear that I like the Giving What You Can pledge that EA folks have been promoting. I’ve been trying to commit to tithing over the past year and would welcome some help getting me over the edge. The main obstacle is that I got divorced this year and since then haven’t quite been able to break even with monthly expenses, and instead have been reducing my retirement and HSA contributions to pay the bills.

That all said, these Giving Pledges (where a billionaire publicly commits to give away some meaningful percentage of their wealth) are, at best, extremely misleading.

SBF benefited from the PR glow from making his own version of the commitment. He was constantly introduced as the “billionaire who made all his money to give it away.”

And so some meaningful percentage of people respond to these pledges by thinking something like, “Wow, these billionaires are pretty generous people. They could be living a lavish life, but instead they’re selflessly giving away all their money. Thanks, Bill Gates!” Many of the journalists covering SBF fell for it.

The problem: it’s more or less impossible to personally consume more than tens of millions of dollars a year in luxuries. You have to give it to other people. And everybody does and always has. The only interesting question is: how are you giving away the money?

Consider the three following strategies:

- Employ thousands of people to work on your pet projects. These projects may or may not turn a profit but that’s not going to be your primary concern.

- Give the money to your heirs. Pay a heavy estate tax back to the government when you die. Encourage your heirs to be good people and to steward their wealth wisely. Maybe they’ll have more time to learn how to be good donors than you do as an active billionaire entrepreneur.

- Give the money back to the government (let’s say, writing checks to federal state governments over the course of your lifetime so there’s no one-time tax windfall that could create perverse incentives) and allow the democratic process to determine where it gets put to use.

Now, when billionaires sign the Giving Pledge, it’s mostly a form of #1. Certainly it was in SBF’s case. He had very specific projects that he funded (newspapers, pandemic preparedness, AI research, building the Effective Altruism community, a new university, etc). He commanded people to work on these projects with his money (and FTX customers’ money, of course). I view that as a form of wielding power. I don’t consider that generous.

#2 is the default option. I’d argue that it’s actually more generous than #1. It requires you to (1) raise good children, (2) pay your taxes, and (3) relinquish control. But it doesn’t qualify you for the Giving Pledge.

An #3 is clearly the most generous. You’re giving away to the whole society without asking for anything in return. It also has the pro-social property of encouraging the ultra-rich to feel invested in an effective democratic process so that their money gets put to good use.

But who’s signing the “Give It Back to the Society that Produced Me With No Strings Attached Pledge”? That’s what we should demand.

Until then, it is a horror that so many of us fall for these pledges.

Horror 4: “Earning to Give”

I know this idea doesn’t need my help to die out. If you want to be rich and powerful, “Earn to Give” gives you a truly toxic veneer of altruism with which to cover your ambition. As we have just seen.

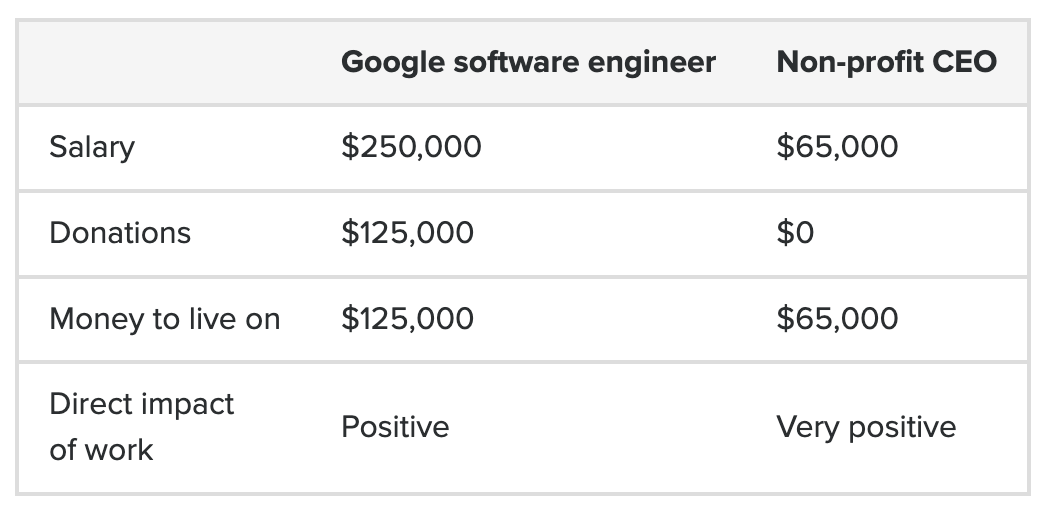

For illustration, here’s the EA website section on Earn to Give, where SBF was featured until yesterday. It gave the case study of Jeff, who left his job as a non-profit researcher to work at Google:4

Jeff can live on about two times as much as he would have earned in the nonprofit sector, and still donate enough to fund the salaries of about two nonprofit CEOs. On top of this, he may also have some positive direct impact too, since Google has developed valuable innovations like Google Maps and Gmail; and he thinks he’s happier in his work because he enjoys engineering.

This is their best example for Earn to Give.

Notice some gaping holes:

- What if Jeff would like to found a nonprofit that otherwise wouldn’t exist without him and which he is uniquely qualified or passionate to run well?

- What if, by his example, Jeff encourages his friends to join him at his nonprofit and therefore increases the chances of it succeeding?

- What if Jeff learns valuable lessons at the nonprofit and increases the collective understanding of an important social problem?

- What if Google starts employing him to engage in monopolistic, rent-seeking behaviors and unwanted customer surveillance? Will that negative outweigh the positive of his donations?

I’m not saying that “generic nonprofit CEO” is the right answer for Jeff. These are hard questions. Every day, people struggle with the choice of jobs and careers for this reason. There’s all kinds of advice out there. But I would never start with “Earn to Give”. I’d start with “Live virtuously, and try to find a career where your virtues can shine. If you want to focus on making money, that’s not wrong and it can give you a lot of freedom, but beware of the ways it can corrupt you.” Or something like that.

Horror 5: The phrase “Effective Altruism”

I just want to focus on the phrase, “Effective Altruism,” not the community.

Suppose we divide the world into two groups, people who are Effective Altruists and people who aren’t.

If you’re not an Effective Altruist, then you must either be (1) not Effective, or (2) not an Altruist. You are either stupid or evil.

This framing is a huge problem. And I think it creates and attracts arrogance.

Such a high degree of arrogance, for example, that they believe they were the first ones to think about how to have a career that aligns with their morals. From the 80,000 hours podcast1:

Rob Wiblin: It’s super fascinating that it’s such an obvious idea to be like, “Well, I’m going to spend all this time in my career during my life. I have particular moral values. What do my moral values say would be the best thing to do?”

Sam Bankman-Fried: Right.

Rob Wiblin: Especially being open-minded about that and really thinking it through, it just was so uncommon — even for someone as incredibly smart as yourself. Basically no one was really thinking this way until kind of at least the 2000s.

Sam Bankman-Fried: I think that’s basically right. And I agree, it’s sort of weird and confusing.

I’ll just end with Glen Weyl’s take on EA, which gets into some of the other critiques above in a characteristically brilliant way:

Altruism presumes there is some of cases where people are acting in their "self-interest" and another set of cases where their goal is "the common good". I don't think either thing exists. Almost all our good emerges from shared infrastructure and almost none of that

— (((E. Glen Weyl))) stands with 🇺🇦 and 🇹🇼 (@glenweyl) November 10, 2022

A Final Thought

I like a lot of the ideas I’ve seen bounced around in the EA world. At the very least, they’re provocative. But on the other hand, some of there are quite dangerous. And we know that the EA demographic is extremely homogenous: white/young/high-IQ/male.5 This whole episode is making we wonder if the world wouldn’t be better off (on folk consequentialist grounds!) if the community just decided to splinter out and integrate into other kindred charitable organizations, especially those that focus on cultivating good virtues in practice. I think Unitarian Universalist Churches, for examples, are very smart but underrated amongst this crowd and could use some youthful energy.

-

https://80000hours.org/podcast/episodes/sam-bankman-fried-high-risk-approach-to-crypto-and-doing-good/#transcript ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/23462333/sam-bankman-fried-ftx-cryptocurrency-effective-altruism-crypto-bahamas-philanthropy ↩

-

https://www.samharris.org/podcasts/making-sense-episodes/303-the-fall-of-sam-bankman-fried ↩

-

https://80000hours.org/articles/earning-to-give/ ↩

-

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/ThdR8FzcfA8wckTJi/ea-survey-2020-demographics#EA_Survey_2020__Community_Demographics ↩